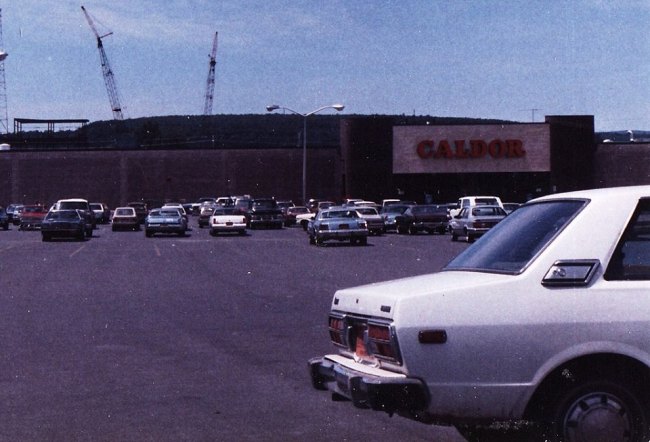

Photo by Yoni Brook via The Night Heron

When people talk about how a city is “real,” they’re talking about the parts that make it a little dangerous. Places that have been abandoned, whether by rules or by people. Times Square before Disney. West Chelsea before the High Line. Hell, the High Line before the High Line. Authenticity is at the center of conversations within historic preservation, urban development, and placemaking. We want our places real, but not too real. Especially not if we have to live there. But if we don’t use a place — really live in it — we get ruins at best and lost history at worst. Is that enough? Do we need abandonment for authenticity?

A city’s lifecycle includes a certain amount of abandonment. A building outlives its usefulness, a factory closes, a tenant moves out. Abandonment may not be so deliberate as it is a disconnect between timing and value. It doesn’t make sense at this particular point in time, for this particular cost, to use this building. Even Ellis Island was abandoned.

NPS Photos – Ellis Island Before and After Restoration.

The Tenement Museum, in New York City, sits between restoration and abandonment. The detail I remember best is the portrait of FDR on the wall of one of the apartments. It hung there through the Great Depression and for another 50 years after its owners moved out. With too many fires destroying buildings’ only route of escape, New York City updated its codes to outlaw wooden staircases. The landlord couldn’t afford to put in metal stairs, so the building sat empty until it was rediscovered, now a time capsule. The museum has since restored several of the apartments, telling the personal stories of the families who lived there. They’ve also kept some apartments as stabilized ruins, just as they were when the museum founders discovered the mothballed building. Bare wood, cracked plaster, peeling wallpaper, closer to authentic. Closer to abandoned.

Our experience and perception of public space, history, and abandonment has been changed by photography and the internet. There are Facebook pages dedicated to old photos of places past their prime. Urban spelunking photography is now its own genre, museum exhibits and all. You can even take tours of abandoned places, some more dangerous than others. It’s turned into its own industry in some places. We can see the process of decay and we must really like it. By sharing images of abandoned places, are we making them public again? Taking ownership of them?

At the intersection of abandonment, urban spelunking, and public art, is the Wanderlust School of Transgressive Placemaking. Their most recent project was a complete reimagining of public space — a speakeasy inside a water tower atop an abandoned building in Manhattan. There was a band. There were drinks. The bar, tables, and chandelier were made of piano parts. Your ticket was a pocket watch that only a friend who had been their previously could give you. Just read Dan Glass’s story about it in The Atlantic Cities. A closely related group, Wanderlust Projects, led an exploration of Brooklyn’s abandoned Domino Sugar factory and held a jazz show in an abandoned Pennsylvania honeymoon resort. Now they’re starting a series of talks on urban exploring and remaking invisible places. Is this the next wave of public art? Adaptive reuse? Temporary preservation? Whatever it is, I want more.

Photo by Yoni Brook via The Night Heron